Our minds are filled with an overwhelming amount of certainty and argumentation. This is especially true in an age where information is abundant and our social reach is vast. We are continuously bombarded with many new ideas, and it becomes difficult to understand what is true. We may recognize ideas that support concepts we already have, while others conflict with our current ones. However, these new ideas, regardless of how well they align with our own, often feel reasonable and valid. How can so many conflicting ideas all seem valid at the same time?

The sheer volume of information leaves us overloaded, and we tend to respond in one of two ways: we either ignore the topic entirely or we ground ourselves to one perspective. The first response leads to a kind of practical ignorance; an active decision to dismiss the attempt of learning because it is easier and less overwhelming. The second entrenches one in a single viewpoint, making one defensive rather than open. Yet neither response is necessary. We can step back from any single lens and begin to see the world through multiple points of view. This is the essence of framing; it explains why many different ideas and perceptions can make sense.

Framing

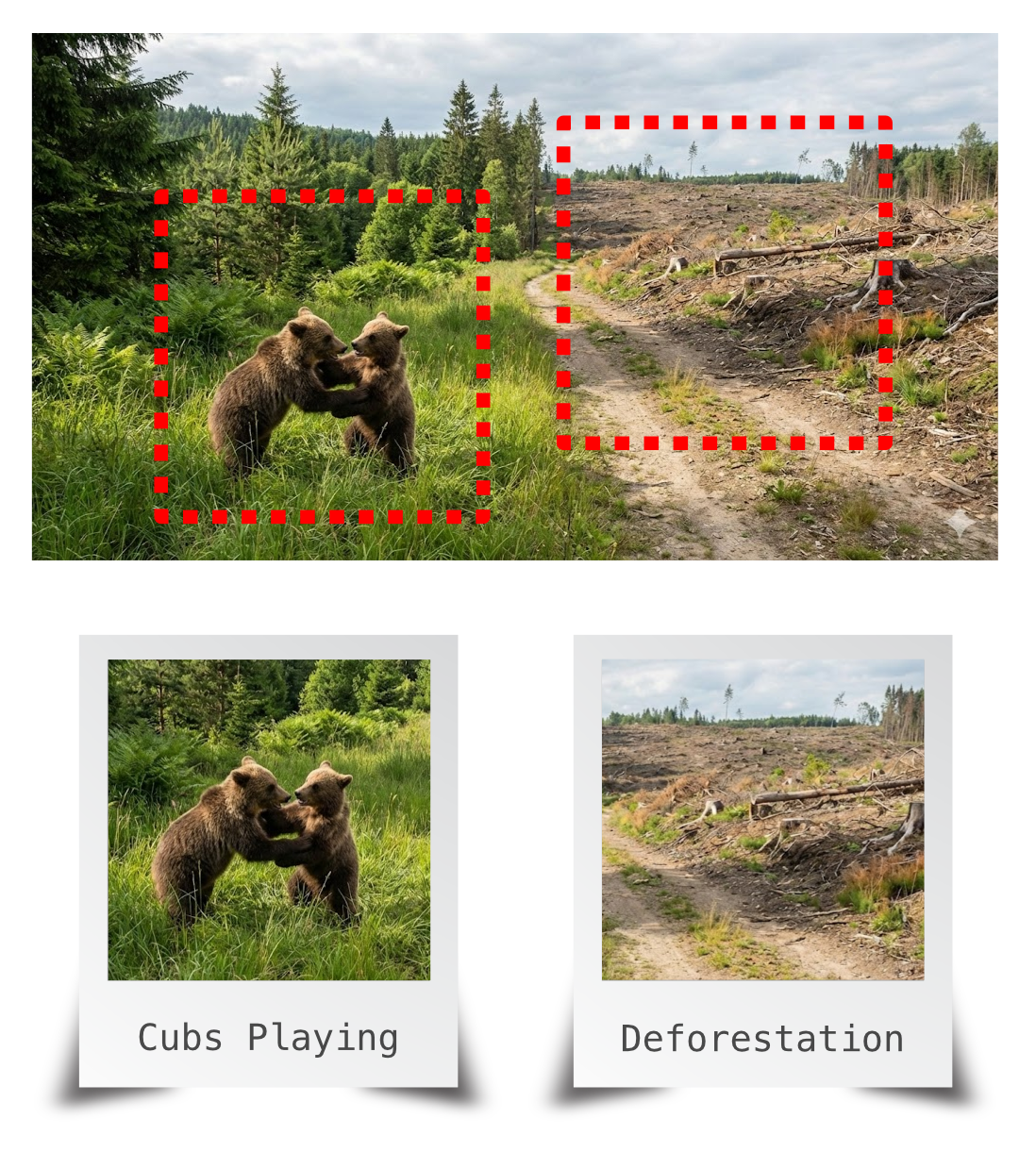

The word framing is useful for describing this phenomenon because it naturally evokes a visual image. Think about a photographer pointing a camera at the world. They don’t want to capture every detail of the scene, they want to capture the story they envision. They adjust the zoom level and focus on selected elements. Let’s imagine a photographer taking pictures in nature. They stumble upon two bear cubs playing in tall grass and take a picture of it. However, to the right of the cubs, there is residue of human deforestation, and they take a picture of that as well. When the photographer presents to people the two pictures, it is hard to tell that they both come from the same place. One is full of life and enjoyment, while the other is destruction and loneliness. If the photographer zoomed out, only then we would see a larger view of the scene. But, if they did, we wouldn’t have such compelling stories from the photos.

This concept transcends to our ideas as well: we frame them in a way that tells a good and meaningful story. We take facts and frame them in a way to demonstrate only what we care about. A common example is a cup of water. When someone says a cup of water is half full, they are seeing the situation optimistically. However, someone else may say the cup of water is half empty, seeing the situation pessimistically. Nonetheless, both ways of describing the cup of water are valid, they just tell a different story. The fact is, the cup is filled half way with water. How we want to interpret that is based on how we frame it.

We can go even further and see how other frames may describe this cup of water. A physical frame may describe it as H2O in a cup. A chemical frame may describe it as a universal solvent capable of dissolving ionic compounds. A thermodynamic frame may describe it as a liquid in equilibrium between vapour pressure and ambient temperature. A biological frame may describe it as a requirement for sustaining human life. An economic frame may describe it as a commodity with a price. A social frame may describe it as hospitable, a gesture of offering someone a drink. A psychological frame may describe it as a symbol of calm, simplicity, purity, or clarity. The list goes on.

The purpose here is to show that all these interpretations are different, yet each contains its own truth. Based on the story one wants to tell, one will frame their theories around it. As a chemist, for example, it doesn’t benefit their experiments to know the psychological perspectives or the economic ones. They’ll describe water in terms of chemistry. It is a matter of adjusting lens and setting the right amount of zoom and focus.

How Can Two Conflicting Ideas Be Correct

Let’s go back to the example of the bear cubs and the deforestation. How can two conflicting photos describe the same place? The photographer framed each scene so that the two environments never overlapped. As a result, the photos feel completely separate from one another. We do the same with our theories. We frame them in such a way that two theories might feel conflicting, yet they are describing the same concepts.

The danger here is becoming attached to a single interpretation. If the photographer shows one person the bear cubs and another the deforestation, and tells each that this is an accurate representation of the place, each will walk away believing a different “truth.” If they have a discussion of the place, they would be dumbfounded by each other’s ideas. How can one say it’s full of life and joy, while the other is saying its destroyed and empty? One may become defensive, frustrated, even angry at this point.

Let’s walk through a more concrete example of two conflicting ideas. Let’s imagine a situation where a nation’s report just disclosed statistics for unemployment. The first journalist is going to report the statistics in terms of unemployment rate. The data shows that unemployment rate has gone down, meaning the percentage of people without jobs compared of the total labor force has decreased. The journalist will report the findings as a positive success of the nation. However, if the labor force grows faster than the number of unemployed, the rate can go down even if the number of jobless people increase. If more people are joining the workforce, some of those are working while others are unemployed, there can be an increase in number of unemployment, even though the percentage of unemployed people decreases. This journalist framed the story in terms of proportion. Another journalist, however, is going to write a piece based on the count. Sifting through the data, they found that more people are unemployed. This is the absolute number of unemployed individuals in the nation. So, if population increases or more people join the labor force, the raw count can rise even if the rate falls. This journalist will report it as a failure of the nation because they framed it in absolute quantity.

As you can see, confusion may arise when different people take one or the other article seriously. Some will advocate without a doubt that unemployment is getting better, while others are bewildered, since it is clear that it is getting worse. However, both perspectives are valid based on the frame. Neither journalist framed the argumentation to include both proportional and quantitative analysis. Thus, the simplicity of the idea causes ignorance on topics that haven’t captured a wide enough picture.

What Makes a Good Theory

A more comprehensive theory tries to keep the frame as broad as possible to explain as much as possible. By doing so, the scope of the theory expands, and our understanding of the topic deepens. Using the previous example, if the journalist would break down both perspective and discuss them equally, one would take away a deeper understanding of the nations unemployment. In this case, the journalists can expand the breadth of their theory to include both the proportional and quantitative frame. By doing so, we avoid conflicting and contradicting ideas from the same source. This is what makes a good theory.

Philosophers do a great job of building the widest frames around their theories. They do so because they don’t want their theories and understanding to collapse into contradiction. They also want to reduce the number of assumptions needed to make sense of their theories. This is why masterful philosophical doctrines are so elegant: they aim to account for as much as possible within a single, coherent frame.

For example, let’s take Kant’s moral philosophy. Kant framed ethics around universal principles that transcend culture. He didn’t frame his theories on just the world around him, he expanded it worldwide. There’s also Nietzsche’s theory of values, which frame morality in terms of psychology, history, culture, and power. There are many more examples, but the point is great philosophers often produce maximal frames, the broadest possible structure that can explain the most phenomena at once.

Other professions are good at creating large frames as well. Good historians take economic, political, psychological, cultural, and environmental factors into consideration when framing their theories. Judges and legal scholars try to widen the frame in the justice system to include as much reasoning as possible to produce consistent and principled rulings. Scientists also try to work with large frame to create universal theories that cover many domains in the sciences. There are many more professions that make great theories.

The Limit of our Knowledge

No matter how elegant or all-encompassing our theories are, we may eventually find them to be wrong or incomplete. This happens precisely because frames exist in the first place. It is impossible not to utilize frames because of the limitations of our understanding of the world and universe. Some limitations are only temporary; we may discover them eventually, just not at the moment the theory is created. This happens often throughout history. Once we discover a new concept, we try to expand our current theories to encompass it.

Let’s go back in time when the world was thought to be deterministic. All theories were based on the capability of predicting the future through equations and understanding natural laws. Even rolling a die, knowing all the right parameters, would be deterministic. Probability was seen as an illusion, a lack of understanding all the circumstances of an event. However, we discovered quantum mechanics and it proved that the world operates on true probability. Much of our understanding of the world collapsed. Although the frame was large, it failed to encompass the behaviours of quantum mechanics. New theories emerged, and our understanding of the universe broadened.

An interesting outcome is old theories are still useful, depending on the issue at hand. If the problem being solved fits nicely in old frames, we can use the older theories. We see this all the time in sciences and other fields. A theory isn’t necessarily right or wrong based on the breadth of its frame. Sometimes pragmatism is needed, and if it involves a smaller frame, so be it.

Lastly, the concept of frames mean we don’t know what we don’t know. We frame our theories because we don’t know everything. This is the first limitation of our knowledge. Another limitation is that framing may always be necessary, no matter how advanced our theories become since we are limited beings. We are limited by our five senses, by our processing power, by our resources, and other limitations. There could be aspects of our world and universe that we will never be able to understand. There are some concepts and truths that will always be far from our grasps. We may always need to frame our theories around the limitations of our current knowledge and capabilities.

What to Do With All This?

Some theories are valued and framed around a small subset of our knowledge. Some theories are less useful, yet these theories frame a large portion of our knowledge. The size of the frame doesn’t make it useful or useless. Depending on the objective, a smaller frame may help make better decisions. Conversely, in other instances, one will need a larger frame. However, the opposite may be true as well. Smaller frames may create horrible theories, while larger frames create helpful and universal theories. The point is to be able to recognize the frame and understand its limitations. Every time you discover new ideas or theories, try to identify the frame. You can either choose to attempt to widen the frame, or elaborate the current theory within the frame.

By doing so, you can become less ignorant and avoid utilizing your defence mechanisms. You avoid anchoring yourself to any one theory, treating it as correct and dismissing all others as wrong. You understand the limitations of the theories, finding no need to defend it. You also understand when two valid theories contradict, you must simply expand the frame. Exploring ideas becomes more fascinating. Recognizing the elegance of great theories become more awe-inspiring.